Borderless Oceans, Indigenous Guardians

"When water flows, it doesn't stop at a sign. Nature needs to do what it needs to do and we need to help that process, not hinder that process." -Betty Osceola

One Ocean, Many Voices: How Water Connects Us All

The ocean flows beyond borders, linking cultures, histories, and generations in its vast embrace. Across the world, Indigenous communities have long understood that the ocean is more than water—it is a living, breathing entity that carries the voices of ancestors, shapes creation stories, and sustains life. From the icy currents of the Arctic to the warm tides of the Pacific, the ocean is revered as both a guardian and a guide.

In many Indigenous languages oceans are poetically described as “great water”, “mother ocean” or “endless water”. Variously described as in Hawaiian (ʻŌlelo Hawaiʻi): Kai (sea) and Moana (ocean), and Inuktitut (Inuit): Tariuq, oceans are held as sacred, living entities guiding spiritual life and creation stories, ancestral and deity worship. Some coastal nations, such as the Coast Salish-speaking people and Tlingit tribes of the Pacific Northwest believe the ocean is a provider and protector, essential for maintaining balance in nature and human life. The ocean in the Inuit culture of Arctic Alaska and Canada is often considered a place that connects them with the spirits of their ancestors. Chumash (Central and Southern California Coast) has spiritual beliefs tied to the ocean's cyclical nature and the interconnectedness of all life. The ocean is seen as a mirror of the human world, reflecting balance and harmony when treated with respect. In Hawaiian and Polynesian cultures, the ocean is sacred, and rituals are performed to honor ocean deities like Kanaloa, the god of the sea, and to ensure safe passage over the waters. Their stories, or mele, are often about the ocean, its creatures, and the spiritual meanings tied to it. There are often expansive words or even sentences to describe oceans as they are seen to have layered meanings – from practical, everyday sustenance to ancestor worship and sacrality of the interconnectedness of all life that oceans sustain.

James Vukelich Kaagegaabaw here explains the word for ocean in Ojibwe

Languages carry the wisdom of the ocean’s borderless nature. In Māori, wai pounamu means "greenstone waters," connecting the shimmering coastal hues to pounamu, a sacred jade-like stone. The name Te Waipounamu, the original name for New Zealand’s South Island, reflects this deep relationship between land and water, a reminder that the ocean’s presence is woven into daily life.

This deep reverence for the ocean translates into responsibility. Indigenous peoples across the world see themselves as stewards of the sea, protecting it not only for survival but as a way to honor their ancestors and future generations. The ocean provides, teaches, and connects—and in return, it must be safeguarded. As we move forward, learning from these traditions can guide us toward a more harmonious relationship with the waters that sustain us all.

Join us for Global Indigenous Futures at WITH Festival on February 21st, 2025, virtually and in person. Registration is free, at this link.

Tales the Tides Carry: Ocean Myths from Around the World

The ocean knows no borders—its waves touch distant shores, carrying the stories of those who live alongside it. Across cultures, the sea has inspired myths, legends, and rituals that reflect humanity’s deep connection with water. These stories tell of powerful deities, protective spirits, and mystical creatures, shaping the ways communities navigate and respect the ocean.

In East Asia, the ocean is revered as the domain of the Dragon King, known as Longwang in China, Yongwang in Korea, and Ryūjin in Japan. These powerful beings rule over tides, storms, and marine life, ensuring harmony between land and sea. Temples dedicated to the Dragon Kings have long stood along coastlines, where fishermen and sailors offer prayers for safe passage and bountiful catches. Their continued worship reflects the enduring relationship between people and the ocean. Japanese folklore also warns of the Umibōzu, a mysterious and terrifying sea spirit. This towering, shadowy figure with a bald head is said to appear on calm waters, only to summon violent storms and capsize ships. According to legend, sailors who encounter Umibōzu must either remain silent or offer it a bottomless barrel to avoid its wrath.

Similarly, in Southern China, the sea is protected by Mazu, Goddess of the Sea, who was once a human named Lin Mo. Believed to warn sailors of approaching storms, Mazu is worshipped in coastal communities from Fujian and Macau to Vietnam, Malaysia, and the Philippines. Her influence has even crossed the Pacific Ocean, as Chinese migrant communities built Mazu temples in the United States, ensuring that her protective spirit travels with them. Indonesia’s Nyai Roro Kidul, Queen of the Southern Sea, commands waves and storms, with legends warning against wearing green near her waters. Across India and Southeast Asia, Nāga serpent spirits guard oceans and rivers, controlling rain and water balance. Japan and China tell of the Giant Kraken of the East, a monstrous cephalopod capable of sinking ships. In Taiwan, the Flying Fish Spirit is sacred to the Tao people, guiding sustainable fishing practices.

The Bajau Laut, often called "Sea Gypsies," are an indigenous group in Southeast Asia who have lived on the waters of the Coral Triangle for centuries. Their deep connection to the ocean is reflected in their spiritual beliefs and practices. They believe that the sea is inhabited by spirits, and rituals are performed to honor these beings and maintain balance in the marine ecosystem.

One such ritual involves "feeding the sea," where offerings of rice, fish, and other items are cast into the water to appease the spirits and ensure a good harvest. The Bajau’s sustainable fishing practices, passed down through generations, demonstrate an intuitive understanding of ocean stewardship that aligns with modern conservation principles.

Balinese Hindus perform numerous rituals to honor the ocean and its deities, such as Baruna (the god of the sea) and Dewi Laut (the goddess of the sea). These rituals often involve offerings and ceremonies to maintain harmony between humans and the ocean, ensuring its health and abundance. While Dewi Danu is not directly associated with the ocean, her role as a water goddess complements these practices. The Balinese philosophy of Tri Hita Karana (harmony between humans, nature, and the divine) underpins the island's approach to environmental conservation. This philosophy extends to the ocean, where communities work to protect marine ecosystems through traditional practices and modern conservation efforts. Dewi Danu's stewardship of freshwater resources can inspire similar care for the ocean. An important ritual is the Nyepi Laut (silent day of sea) which is dedicated to show respect to the sea for the bounty it provides by giving it a rest for a day. All activities related to the sea and ocean such as fishing, tourism swimming are all prohibited for a period of 24 hours.

For the Māori of New Zealand, the ocean is not only a path but a living force. Tangaroa, the god of the sea, connects the Māori to the water’s spiritual and physical power. Traditional waka canoes were guided by the stars, symbolizing the ocean as both a passageway and a sacred realm, where the deep blues of the sea reflect the vastness of their journeys.

Across the world, the sea’s vastness is also personified in Aegir, the Norse god of the ocean. With his deep blue complexion, he embodied both the beauty and fury of the waves, throwing great feasts for the gods while reminding sailors of the sea’s untamed power. Similarly, in ancient Greece, Poseidon, known as Kyanochaites (“dark-haired, dark blue of the sea”), ruled the waters, his essence tied to the Mediterranean’s vast and mysterious depths. The Nereids, gentle sea nymphs, guided sailors, while sirens lured them into danger—capturing the ocean’s dual nature of allure and peril.

In Aboriginal Australian traditions, the ocean’s shimmering blues, greens, and reds reflect the scales of Wanampi, the Rainbow Serpent, who carved the rivers and seas, shaping the land itself. Meanwhile, in Scotland, sailors feared the Blue Men of the Minch, supernatural beings who conjured storms and tested captains with riddles, their fate determined by their answers.

The Slavic waters, too, hold secrets. Vodianoi, with their green beards and slimy, scaly bodies, ruled underwater palaces, dragging swimmers into their depths. Often linked to the Rusalka, spirits of drowned women, these beings reminded people of the ocean’s hidden dangers.

Though these myths come from different corners of the world, they share a common truth—the ocean is alive with stories. Just as the tides carry water between continents, so do these legends connect us across time and place, reminding us that the sea belongs to no one, yet belongs to us all.

The ocean is more than just water—it is an ancestor, a provider, and a sacred force that sustains life. These deep-rooted beliefs shape how Indigenous communities interact with the sea, viewing it not as a resource to be exploited but as a living entity that must be protected. From Pacific Island navigators who honor the currents to coastal First Nations who practice sustainable fishing, Indigenous stewardship is guided by respect, reciprocity, and responsibility. Their traditions remind us that caring for the ocean is not just a duty but a way of life—one that ensures its survival for future generations.

Guardians of the Blue: Conservation, Community & Indigenous Knowledge

Historically ocean stewardship has been extractive, often exploitative, consumption-driven, and restricting the rights of indigenous communities. Some of these colonial, unequal relationships are now changing largely due to the efforts of different First Nation groups across the globe. Increasingly now stewardship, conservation, and relationships between humans and ocean and marine life center what indigenous scholars Jacobs, Avery, Salonen, and Champagne call the Indigenous Value Systems made up of the seven Rs – Relationship, Responsibility, Reciprocity, Redistribution through reconciliation, Respect, Relevancy, and Rights. In a similar vein, a working definition of stewardship discussed by Enyew, Poto, and Tsiouvalas shows that the Maori people of New Zealand define stewardship as kaitiakitanga translated as “guardianship, preservation, conservation, fostering, protecting, and sheltering. The guardians of the natural world and its domain are the Papatu¯a¯nuku (Mother Earth), the Ranginui (Father Sky), and their many children, including Tangaroa (the Oceans). Human beings (ira tangata) play a role as kaitiaki (caretakers) and have an obligation to nurture and protect the physical and spiritual well-being of the natural systems that surround and support them.14 Kaitiaki are agents that perform the task of active guardianship and are charged with the responsibility of safeguarding and managing natural resources for present and future generations. Decisions enacted by the kaitiaki are based on inter-generational observations and experiential understandings.” (pp. 209-210)

Two-Eyed Seeing and Co-Stewardship

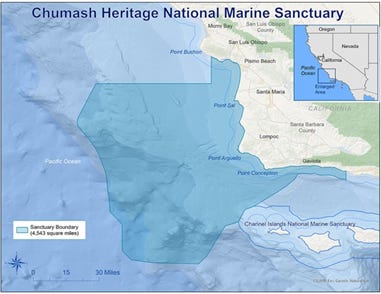

NOAA’s National Marine Life Sanctuaries in partnership with different Indigenous tribes, has developed a model of partnership which they call co-stewardship where the two entities collaborate and cooperate on technical expertise, resources, improve resource management, including Indigenous knowledge, values, and experiences in protecting and stewarding ocean marine systems. The Chumash Heritage National Marine Sanctuary is an example of this co-stewardship, placed in operation from November 2024. Respect is central in guiding this collaboration, where NOAA pledges and recognizes the more than 10,000 years of existence of the Chumash people in the central California coastal region, and gives the community the lead in steering and protecting the futures of this ocean region.

Two-Eyed Seeing is a modern Indigenous response to the challenges faced in shaping sustainable responses to the conservation of the ocean. According to “Elder Albert Marshall of the Mi'kmaw as Two-Eyed Seeing, where one eye views the world through a lens of Indigenous knowledge and the other through Western ways of knowing.” (Jewett, 2023)

The recognition and value given to Indigenous communities is a recent development and has come from decades of Indigenous community activists calling for a move away from a “manifest destiny” form of colonial extractive and exploitative relationship with land, people, and oceans to what Indigenous scholars call a new de-colonial Indigenous value system of conservation which centers two-eyed seeing, reflexivity, storytelling, symbology, and beading. This is a multi-dimensional holistic approach with seamless connectivity between humans, culture, and nature – emphasizing a borderless continuum of ocean conservation and human existence.

An example of this recognition is the Northern Bering Sea Climate Resilience Area shepherded by Alaskan tribes and recognized by an executive order of President Biden in 2021, where Native Alaskan authority is to be respected and followed in marine stewardship. The order also permanently withdrew areas in the Northern Bering Sea from oil and gas leasing. The Bering Sea Elders group, and Association of Village Council Presidents, among others, were responsible for this executive order to be passed.

Future Pathways and Indigenous-Led Success Stories in Ocean Stewardship

Local and Traditional Ecological Knowledge (LTK) – Currently there is an emphasis on using marine LTK to develop stewardship strategies, improve conservation management plans, and resolve conflicts and disputes.

An example of the use of LTK can be seen in the way in which the Haida Gwaii’s First Nation’s lens is used to co-manage Canada’s Department of Fisheries and Oceans.[1] For an in-depth understanding the use of LTK see the Coastal First Nations network’s (The Great Bear Initiative) work on stewardship.

Co-Producing Sustainable Ocean Plans (SOPs) with Indigenous and traditional knowledge (ITK) holders - Lead experts in the field both from Western scientific community and Indigenous scholars and practitioners increasingly recognize that any SOP moving forward should be inclusive and equitable, local/place based and value multiple knowledge systems to solve and plan future stewardship and conservation of oceans. In-depth analysis (Blue Paper titled “Co-Producing Sustainable Ocean Plans with Indigenous and Traditional Knowledge Holders) can be seen here.[2]

Strength in Partnership: How Indigenous Protected Areas is Fostering Collaborative Conservation in Australia

Indigenous stewardship of land and sea has been a cornerstone of conservation efforts for thousands of years, ensuring the sustainability of ecosystems while maintaining deep cultural connections to the Country. In Australia, Indigenous Protected Areas (IPAs) have become a vital tool for First Nations-led conservation, with over 90 million hectares of land and 6 million hectares of sea managed by Traditional Owners. These initiatives, supported by government funding and Indigenous ranger programs, combine ecological knowledge with modern conservation science to protect biodiversity, restore damaged ecosystems, and safeguard cultural heritage. The expansion of Sea Country IPAs underscores the importance of marine conservation, with projects focusing on reef restoration, seagrass monitoring, and the protection of threatened species such as dugongs, sea turtles, and sawfish. By integrating practices like cultural burning and catchment management, Indigenous communities are not only preserving their environments but also reinforcing their rights to manage and protect their ancestral lands.

Across Australia, Indigenous ranger groups from diverse communities—including the Martu, Nari Nari, Gumbaynggirr, Gunditjmara, and Karajarri—are leading conservation efforts through hands-on management of forests, rivers, and marine ecosystems. These rangers play a critical role in monitoring wildlife, mitigating climate change impacts, and addressing environmental threats like invasive species, coastal erosion, and pollution. In regions like the Fitzroy River, the Great Barrier Reef, and the Kimberley coast, their work is supported by partnerships with conservation organizations, universities, and government agencies. Programs such as the Junior Sea Country Ranger initiative ensure that Indigenous youth are actively involved in the stewardship of their environments, fostering intergenerational knowledge transfer. By blending traditional ecological knowledge with contemporary scientific methods, these efforts highlight the resilience and leadership of Indigenous communities in tackling some of the most pressing environmental challenges.

The success of Indigenous-led conservation is further reflected in the collaborative management of Australian Marine Parks, where Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples continue their sustainable practices under legal frameworks like the EPBC Act. These partnerships recognize Indigenous rights to hunt, fish, and perform ceremonies in protected waters while maintaining ecological integrity. The management of Sea Country goes beyond conservation—it is an assertion of sovereignty, identity, and cultural revival, reinforcing Indigenous governance in environmental decision-making. As climate change intensifies pressures on marine and coastal ecosystems, Indigenous stewardship offers a holistic and proven approach to sustainable management, ensuring that future generations inherit thriving lands and seas deeply connected to their cultural heritage.

Bridging Traditional Knowledge and Modern Conservation: Community-Led Marine Stewardship in East Africa

Across East Africa’s coastal communities, Marine Cultural Heritage (MCH) is emerging as a key driver of sustainable development. In Mozambique’s Chonguene District, social learning is being harnessed to protect coastal cultural ecosystem services from increasing pressure due to agriculture, fishing, tourism, and gas industries. A community-driven initiative integrates local knowledge into education and policy, ensuring traditional environmental practices are passed down through an innovative curriculum and a cultural ecosystem services center. Similarly, in Kenya’s Kilifi County, local communities are taking charge of marine cultural heritage protection by documenting bio-cultural community protocols, strengthening legal recognition of customary governance systems, and preserving traditional ecological knowledge. The development of a GIS database of marine heritage sites informs conservation planning, while awareness campaigns empower local people to sustain their environment.

The Rising from the Depths project is amplifying such efforts by demonstrating the economic and ecological value of MCH across East Africa. It works to integrate traditional heritage knowledge into policy frameworks and economic planning, fostering community resilience and supporting sustainable tourism. By comparing the fisher communities of Kenya and Tanzania, researchers are highlighting the role of Traditional Heritage Knowledge (THeK) in marine resource sustainability, particularly its gender dimensions and links to fisheries governance. This approach not only safeguards maritime traditions but also informs the broader Blue Economy framework, ensuring cultural heritage plays a central role in coastal conservation strategies.

A key contribution of Rising from the Depths is its focus on long-term sustainability and policy influence. By strengthening the legal recognition of MCH and advocating for its inclusion in marine governance, the project ensures that coastal communities can leverage their cultural identity as an economic asset. Through interdisciplinary collaboration with local stakeholders, it promotes heritage-based enterprises, job creation, and environmental stewardship. Furthermore, by addressing climate change challenges through a heritage-based lens, the initiative enhances coastal resilience, supporting community-led conservation efforts and fostering a model for sustainable development that can be replicated across the region.

Some Success Stories

1. Haida Gwaii Marine Protection, British Columbia, Canada: The Haida Nation successfully negotiated co-management of the Gwaii Haanas National Park Reserve and Marine Conservation Area with the Canadian government.

Impact - Increased biodiversity, recovery of rockfish populations, and strengthened Indigenous governance over marine resources.

2. Makah Tribe’s Marine Management & Whale Protection, Washington, USA: The Makah Tribe won legal battles to maintain their treaty rights to hunt whales while implementing strict conservation practices.

Impact - Maintained cultural traditions while ensuring gray whale populations remain stable and protected.

3. Mi’kmaq & Maliseet Lobster Stewardship, Atlantic Canada: Indigenous fishers in Nova Scotia fought for their legal right to practice sustainable lobster fishing under treaty rights. This created a moderate livelihood fishery that balances economic opportunities with marine conservation.

Impact - Increased lobster populations, provided economic independence for Indigenous communities, and set legal precedents for Indigenous fishing rights.

Suggested activity…find more such collaborative, “two-eyed seeing” indigenous ocean and marine life projects around the globe! Send it to us at admin@mediaforchange.org

Think you know the secrets of the sea? Let’s find out!

Indigenous Ocean Stewardship: Films and Books

Films & TV Shows

Whale Rider (2002) – A powerful Māori story about the deep connection between people and whales.

Raven Tales (2004–Present) – Indigenous trickster stories that explore environmental and ocean themes.

Moana (2016) – A Polynesian adventure about ocean balance, way finding, and respect for the sea.

Maya and the Three (2021) – An epic tale rooted in Mesoamerican myths, featuring ocean deities.

Spirit Rangers (2022–Present) – Indigenous siblings protect their national park, including its waterways.

Moana 2 (2024) -Moana journeys to the far seas of Oceania after receiving an unexpected call from her way finding ancestors.

Documentaries

Nanuk of the North (1922) - This pioneering documentary film depicts the lives of the indigenous Inuit people of Canada's northern Quebec region.

People of a Feather (2011) – Examines how climate change affects Inuit life, sea ice, and Arctic ecosystems.

Gather (2020) – A look at Indigenous food sovereignty, including sustainable fishing practices.

Voices of the Pacific: Indigenous Perspectives on Ocean Conservation (2021) – Indigenous Pacific Islanders share their knowledge on marine stewardship.

The Territory (2022) – Indigenous Amazonian activists fighting to protect their lands and waters.

Núh-muh: Ocean Guardians (2023) – California Indigenous tribes reclaim traditional marine conservation practices.

Books

Braiding Sweetgrass – Robin Wall Kimmerer

Indigenous wisdom and environmental science come together to explore nature’s gifts.We Are Water Protectors – Carole Lindstrom

A beautifully illustrated book about the sacredness of water and the responsibility to protect it.Indigenous Pacific Islander Eco-Literatures – Kathy Jetñil-Kijiner & Craig Santos Perez

Poetry and essays on ocean conservation and Indigenous resilience.Climate, Culture, Change – Timothy B. Leduc

Inuit perspectives on climate change and how they understand shifts in ocean ecosystems.The Whale and the Supercomputer – Charles Wohlforth

How Inuit traditional knowledge aligns with climate science on marine ecosystems.

Which of these stories interests you the most? How do they compare to how your own community treats water and the environment?

Write to us at admin@mediaforchange.org.

This Ocean Planet is produced by Media for Change

Contributors to this issue: Sumita Chatterjee, Bhaswar Faisal Khan, Rimi Nandy, & Sohini Sengupta. Carol Reese, a veteran teacher of the gifted, coordinated and mentored middle school students in the Eanes Independent School District in Austin, Texas. Olivia Flynn helps spread the word about This Ocean Planet. Uma Chatterjee is responsible for content layout.